The Owls in the Museum

It's October; if it's not on your mind, maybe it should be. There are owls everywhere. These beady-eyed creatures of the night, symbols of wisdom, and omens of death are popping up on storefront windows, expanding their wingspan across book covers, and sporting as the top mascot for US forest services.

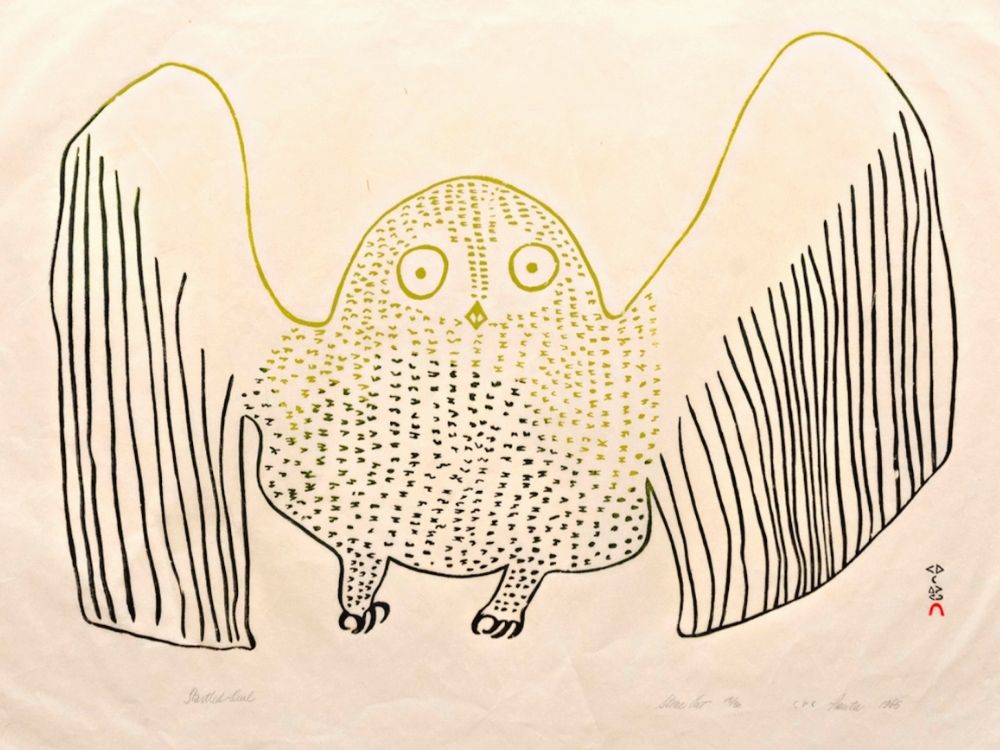

The predominance of owls is no surprise to many of us. From Dionysian Rites to Pokémon, the expansion of owls in legends and myths intercepts many cultures and histories. It's only natural that the stonecut prints from Cape Dorset, currently on view in the exhibition Collective Memories, feature our feathered friends. The collection of prints created by Inuit artists and printmakers in the 1960s and 1970s showcases many, many owls, but why?

This past week, I've been preparing for a curatorial walkthrough of the exhibition, Collective Memories: Stonecuts from Cape Dorset. The exhibition displays 16 stonecut prints that speak to traditional Inuit myths and legends, Unikkaaqtuat. In preparation for this walkthrough, I've compiled notes, read through annotated books, and researched Inuit myths, searching for connections to the depicted mammals, marine life, and birds. The connections are endless. However, to my surprise, the origin myths and accounts of owls were not as frequent or easily found as I anticipated. This did not quite make sense to me, as our collection disproportionately features our feathered friend. Mind you, this could be reflective of my curatorial affections or the affinities embraced by the collecting practices of the donor, Barbara Allen Burns. However, I had a hunch there was more to it. The question changed: If owls are not the center of traditional Inuit myths, what the hoot happened in the 1960s and the 1970s when these prints were created?

The answer, of course, is evident if anyone picked up a holiday catalog from 1965. It is an ookpik!

What is an ookpik? An ookpik is a legendary bird with arctic owl-like characteristics. The name comes from the Inuit word Ukpik which means "snowy owl." Their popularity exploded in the Canadian market due to a 1963 trade show in Philadelphia where the owl-like creature was selected as the mascot. These stuffed big-eyed creatures were instantly popular and quickly materialized as a preferred childhood toy. Essentially, the ookpik was to a 1960s baby boomer what a Furby was to a 1990s millennial, the toy that created quite a stir.

The original artist, Jeannie Snowball, created the design at her Inuit community's co-operative in Fort Chimo (later renamed Kuujjuaq in 1980). Like the Cape Dorset artists, Jeannie's creation of the ookpik reflected her memories from earlier camp life in the extreme arctic conditions. As the story goes, when Jeannie was a child, she was caught in a snowstorm and was starving. An owl landed near her, giving itself to her so she could live. She consumed the owl, and it saved her life. She created the ookpik doll to honor the owl.

In many ways, the market popularity of the ookpik represented the goal of what co-operatives, like the one at Cape Dorset, sought to do: sell contemporary Inuit designs to the western market (also known as "the South") to secure financial/good returns for the original creators at the co-operatives. The instant success of ookpiks caused the design to go viral. A Toronto toy manufacturer won the rights to mass-produce the ookpiks, and it quickly became the "it" toy of the era. The imagery of the ookpiks appeared beyond the stuffed animals to the basic marketing of consumables and household items such as soap bars, wallpapers, and deodorant containers. With each production of the ookpik design, a ten percent royalty was returned to the co-operative as agreed to by the design's licensed copyright.

So, what does this have to do with the Cape Dorset prints? After all, the wall labels in this exhibition reference the images with labels featuring "owls," not "ookpiks" right? The ookpik originated at another co-operative, so the royalties collected did not directly impact Cape Dorset...or did it? This is where the question shifts: Did the sales of the ookpik impact what designs and stonecuts were approved to be distributed at the Cape Dorset co-operative? Or did they impact what designs were most likely to be collected?

The stonecut prints on display in Collective Memories only represent a portion of the stonecut prints created from the 1960s and the 1970s at the co-operative. These prints represent designs that a) were approved by a council and b) were purchased by a collector. Based on the prints distribution model, the stonecuts from Cape Dorset were selected to be distributed to the western market. These prints had to be approved by a specific council, the Canadian Eskimo Arts Council (CEAC). Regulating what could be sold, this council made the executive decisions impacting all Inuit co-operative design production.

During this era, the council's representation firmly reflected Eurocentric values as the council was composed of all white men from "the South" and of European heritage. From this, we can infer that the council was aware of the financial success of the ookpik in the western market. The success of the ookpik likely informed which Inuit designs would sell best in the 1960s and the early 1970s art market and hence which designs were approved. Thus stylistic preference was surrendered to the owl's plump feathered, big-eyed imagery. It is also likely that the western consumer was more likely to buy a print of an owl due to the popularity of the ookpik and its newly coined connection to Inuit culture.

As summed up by reporter Jack McGaw, "The ookpik is about as Canadian as maple syrup. Even though the average Canadian wouldn't recognize an arctic owl even if he saw one at the end of his bed."

To learn more about the imagery and artists represented in Collective Memories: Stonecuts from Cape Dorset, visit the galleries Wednesday through Sunday 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. through December 12, 2021.

###

Read more:

Ookpik, the Canadian Mascot that Went Viral, April, 01, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/archives/ookpik-the-canadian-mascot-that-went-viral-1.5046918

Oopik: Canadian Good Luck Creature by Natalie Ginez, New Jersey Archaeology, July 4, 2017. Accessed October 18, 2021. https://newjerseyarchaeology.wordpress.com/2017/07/04/ookpik-canadian-good-luck-creature/