LaReina Torres '25, one of the Public History students who helped flesh out the history of the High Potential Program, is an HP student herself. “Now, we're willing to speak up about it and have some pride in the fact that we are first-gen,” she says. “We are accomplishing something.” / Photo by Francis Tatem

Student Action Helped Bring the High Potential Program into Being. Fifty Years Later, Student Scholars Are Preserving Its History.

How a program born of protest came to represent “the best of our students”—Gaels past and present tell the story.

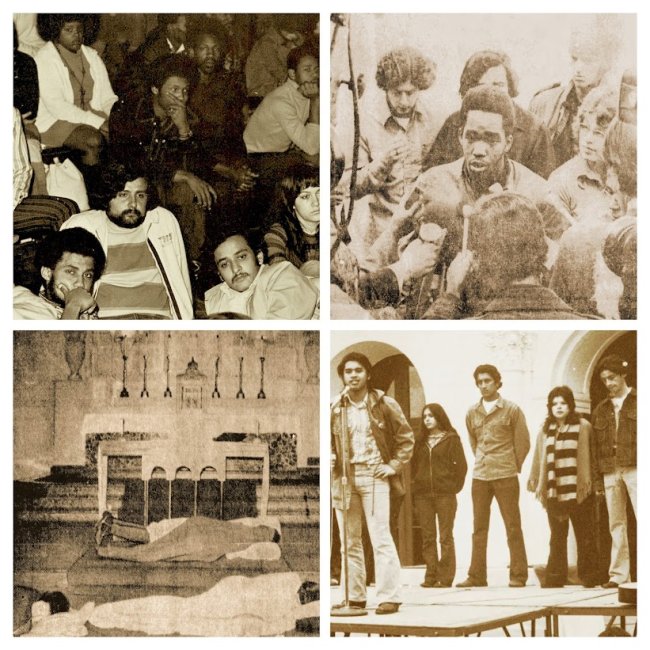

On March 13, 1972, only a few months into his role as Assistant Dean of Students, 22-year-old Tom Brown stepped into the Saint Mary’s Chapel to negotiate with 40 student activists not much younger than himself. Light streamed through the stained-glass windows above him, projecting kaleidoscopic patterns on the walls. Walking down the center aisle, he saw pillows on pews and sleeping bags on the floor around the altar.

The day prior, sophomore Tomas Ramirez ’74 had startled Sunday morning mass-goers by standing up and announcing a peaceful occupation of the Chapel by the Chicano student organization, Moviemento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan (MECHA), and the Black Student Union (BSU). They were protesting a lack of institutional support for “Chicano and Black students,” Ramirez told those present. And they intended to remain there “for as long as necessary,” vowing to go on a water-only fast until the administration addressed their concerns.

It was the latest development in a season of tumult for the College. That January, Saint Mary’s made the controversial move to terminate the contract of Odell Johnson ’58, the popular Dean of Students and first person of color to serve as an administrator in the College’s history. During a February 27 basketball game against rival Santa Clara University, five SMC Black basketball players staged a walkout to protest Johnson’s firing. Then in March, two of the College’s four Chicano faculty members were let go, sparking a rally that drew hundreds of students and community members.

A few days later, BSU and MECHA held a joint press conference, calling out the lack of diversity on campus and emphasizing the need to “implement special programs designed to meet the cultural, personal, and academic needs of Black and Chicano students.” Many of those same MECHA and BSU students occupied the Chapel the following week.

Approaching the protestors, Assistant Dean Brown recognized an irony: Less than a year earlier, he would have joined them. As an undergrad at the University of Southern California, he had served as an early public relations director for the United Committee to Free Angela Davis and took part in the Black Panther Party’s breakfast program, cooking up free meals for Los Angeles schoolkids. He had held a leadership role in his university’s Black Students Union, too. Now, he found himself on the other side, dispatched by the College’s president, Brother Mel Anderson, FSC, to negotiate with the protestors.

Still, Brown was a “stone-cold revolutionary” at heart, he recalls. After he left his meeting with the protestors an hour later, the demands had jumped—from four to ten. When he brought the new list to the President and his cabinet, he recalls the academic vice president shouting, “You threw gasoline on the fire!”

Perhaps. One could also argue that Brown was the right person at the right time. After days of negotiation between MECHA, BSU, and the College, the administration agreed to most of the requests, including increased efforts to recruit people of color as students, faculty, and staff. Brother Mel also committed to increasing the budget for “special programs” to assist students of color along their college journey. He tasked Brown with helping develop these services—an initiative that would, ultimately, become the High Potential Program.

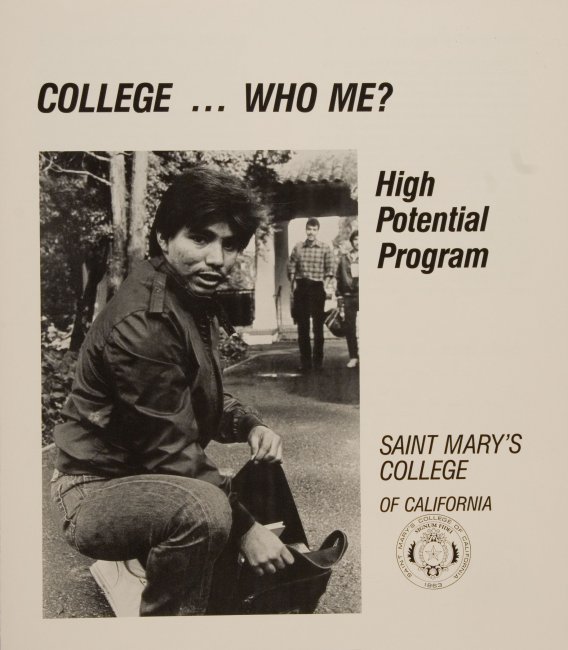

The history of High Potential (HP) is one of progress—in the lives of students and the life of the College. Since 1973, HP has fostered the success of first-generation and low-income scholars, making it one of the longest-running such programs in the country. High Potential began as a three-day summer orientation program for a handful of students; in the years following, it grew to encompass academic workshops, mentorship, success coaching, and above all, social, cultural, and emotional support.

Today, the HP community is worldwide and includes political leaders, educators, lawyers, and one of the very few two-time Oscar winners. For many, the program is the purest expression of the College’s founding mission: to, as Brown puts it, “provide an education for students that might otherwise be denied.”

As the Saint Mary’s community marks High Potential’s 50th anniversary, what Gaels are really celebrating are the success stories of students, past and present. It’s fitting, then, that current SMC students are the ones ensuring those narratives are being preserved.

Filling the Archival Silence

Each year, Saint Mary’s Public History course offers students of all majors the chance to link past to present. Gaels get to go hands-on, delving into historical narratives—from women's experiences of World War II to real-time experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic—and displaying their research in a final exhibit. In recent years, the course has found students partnering with the San Jose History Museum or the Vietnamese American Community Center, gaining real-world (and paid) experience in historical preservation and presentation. And through the efforts of the Saint Mary’s History Department faculty, the College received grants totaling more than $100,000 toward establishing a Public History minor, one of the first of its kind on the West Coast.

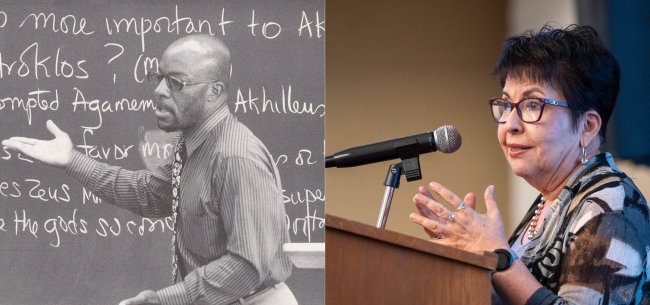

In the spring of 2023, however, the class had Gaels digging into history very close to home: the High Potential Program. The course’s instructor, Professor of History Aeleah Soine, also serves as the Vice Provost of Academic Success, the office that oversees the HP Program. In anticipation of HP’s 50th anniversary, Soine and Jason Jakaitis, then-HP director, soon discovered the lack of historical material. The College Archives held a single file folder entitled “High Potential Program.” Apart from newspaper clippings on the 1972 Chapel occupation and basketball walkout, the folder held little else.

Jakaitis and Soine sensed opportunity. Here was a chance for students to flesh out a vital chapter of Saint Mary’s story for the first time, while inviting others to join in expanding the archival collection further. “It was a project that would allow students to actually practice creating history,” Soine tells me later. “They wouldn’t be just reading and thinking about what somebody else created. They’d be getting into the action themselves.”

While Jakaitis’ Community Media class—also built around public history—focused on creating new video documentation of HP in 2023, the students in the Public History course itself started by combing through back issues of the Saint Mary’s student newspaper, The Collegian. They began working with editions published in 1973, copying and archiving any articles about High Potential, and reaching out to networks of alumni to collect oral histories.

College Archivist Kate Wilson became a key partner in educating the students on what historians call an “archival silence”: when a lack of documentation leads to a gap in the historical record. Wilson also taught how to collect and record metadata for digital cataloging, to make historical sources accessible to broader audiences in the future.

“It was a project that would allow students to actually practice creating history,” says Aeleah Soine. “They wouldn’t be just reading and thinking about what somebody else created. They’d be getting into the action themselves.”

Asking the Right Questions

Soine’s Public History class was tailor-made for students like LaReina Torres ’25. A Chemistry and History double major, she has always gravitated toward hands-on research, she tells me. Growing up, she adored Bones, the Fox procedural drama about grisly crimes solved by examining, well, bones. “By the time I was five years old, I decided I wanted to be a forensic anthropologist,” she says. But her ambitions began to shift at the end of middle school. “I thought, ‘You know what? I think I've grown as a person. I can deal with people who will talk back and sometimes ask questions.’”

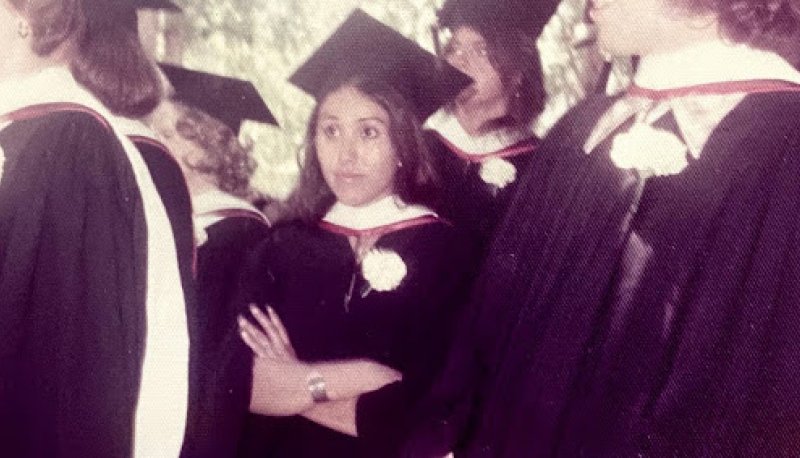

These days, Torres has her sights set on becoming a trauma surgeon. She is quick-witted and self-effacing; it’s easy to imagine her someday cracking jokes and putting patients at ease. In the Public History course, however, she put her people skills to a different use: conducting interviews with HP students past and present. It was fascinating work, and also deeply personal for her. As an HP student herself, she saw her own experience reflected in the lives of those who came before her.

Torres was raised in Madera, California, an agricultural hub in the near center of the state. Her mother is the coordinator of the gift shop and volunteer services at the children’s hospital in town, while her father, who operated forklifts at a string of warehouses throughout her childhood, is currently studying to become an emergency medical technician. Torres is an only child, but it never felt that way. Her maternal grandparents and great-grandmother have lived with them since she was a toddler. “And don't think just because they're older or retirement age that they're going to bed early,” she says. “I never knew what quiet meant.”

The many adults in her life always expected her to attend college. “She’s smart; she’s going,” was the general sentiment, she says. For her, it was more a matter of where—and how. As the first in her family to pursue college, these were looming questions, ones she would largely have to answer on her own.

After applying to a range of schools, Torres ultimately decided on Saint Mary’s. Scholarships, combined with the tight-knit classrooms and culture, were deciding factors, she says. “It wasn’t just what could we afford, but what could I get out of it?” So the where and how had been resolved. But as she transitioned to campus, Torres now faced a whole host of new unknowns. How are you supposed to use the library’s databases? What are office hours actually for?

“When I started, I didn't even know the questions to ask,” she says. “I just knew I needed help.”

That’s where High Potential came in. She first learned about the program at orientation and signed up almost immediately. Soon, she was meeting regularly with her peer mentor, Daisy Guzman ’23, who walked her through “all the unwritten rules” of college. (Example: office hours build connections with professors, which can lead to opportunities down the road.) She was also assigned a success coach, Joy Aburquez MA ’19—now the Associate Director and Lead Success Coach for HP—who has “literally been a joy,” Torres says. Aburquez helped her navigate the intricacies of financial aid, and she regularly emails Torres about internships and job opportunities.

“It’s opened my mind to what I could do and what I'm supposed to be doing,” Torres says. As she began digging into HP in the Public History course, she saw how the Program helped expand the horizons of hundreds of others.

The Cutting Edge

Over the course of Spring 2023, Torres and her classmates tracked down and interviewed dozens of past and current HP students and administrators, working to compile the first comprehensive timeline of the program. What became clear was just how much HP has evolved over the past five decades. “I learned a lot about the program’s early days and growth,” she says. “It was definitely ahead of its time.”

Of course, as Tom Brown will tell you, being ahead of your time means trailblazing without a map. Only in the wake of the civil rights movement of the 1960s had most colleges begun to actively recruit and admit more “minority” students, and the programs created to support them were only a few years old.

In the summer of 1972—a few months after the Chapel occupation—Brown and his colleague, Assistant Dean of Students, Harry Acosta, climbed into Brown’s cherry red Fiat Spider for a whistlestop tour of California colleges. Looking at existing Educational Opportunity Programs and similar initiatives, they visited private Catholic and non-Catholic schools alike, as well as public schools. Brown also visited LaSalle University in Philadelphia and Manhattan College in New York, two Christian Brothers’ campuses with comparable programs. Soon, they began outlining the basis of High Potential. “We recognized that if these students were going to be successful, they needed programs and services to bridge the gap between where they were and where they needed to be,” Brown says.

Many of the services that Brown, Acosta, and their colleagues created for High Potential students would, in time, become part of the fabric of the College itself. First-year and parent/family orientation, academic advising, career coaching, tutorial services, the Writing Center—these were all developed for HP students first. Eventually, Brown would be asked to extend these offerings to the entire campus when Brother Mel promoted him to the newly established position of Associate Dean of Studies.

“We even started the bus!” Brown says. The BART station in Orinda had just been completed, connecting communities adjacent to Saint Mary’s to the new rapid transit system throughout the Bay Area. But commuting students still had to catch a ride to get to campus. “So, we bought an old school bus, painted it red and blue, and called it Saint Mary’s Area Rapid Transit: SMART.” Now, of course, the Contra Costa County bus line runs every hour.

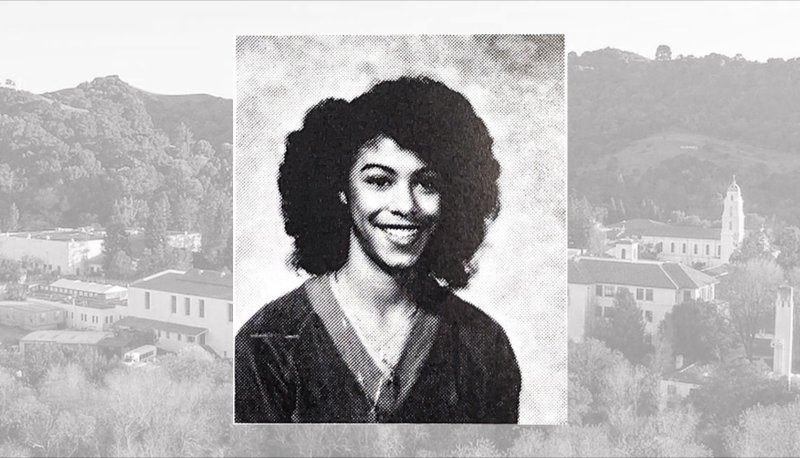

As HP grew, its scope expanded. Where the program had once included primarily Black and Latino students, it now encompassed first-generation and low-income students of all backgrounds. With a grant from the Irvine Foundation, Maria Hernandez—who oversaw High Potential from 1987 to 1994—and Brown hired John Dennis to serve as the first full-time HP Director.

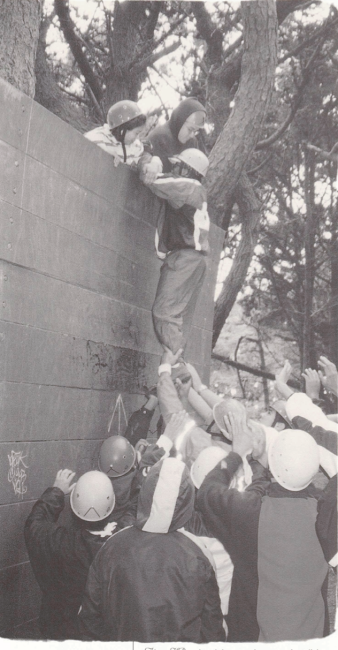

Under Dennis, affectionately known as “Dr. D,” the three-day orientation evolved into a multi-week academic boot camp. Students read and discussed Homer’s Illiad in preparation for Collegiate Seminar and took part in writing workshops. They received sessions on time and stress management. And, most memorably for many, they tackled a ropes course at Fort Miley in San Francisco, where the incoming HP students helped each other “climb the wall.” For Dennis, the exercise spoke to the entire project of High Potential, which “epitomizes the dream of Saint John Baptist de La Salle,” he said in 1988.

The support services were proving successful, too. In her interview with Public History students, Maria Hernandez recalled an HP graduation rate of 84% during her tenure. She credits her students’ tenacity, as well as the concentrated attention and encouragement they received from staff and faculty. “As a first-generation, college-bound kid, you really do depend on the grace and generosity of strangers,” she says. “I knew that firsthand.”

With Saint Mary’s entering the 2000s, HP continued to set a standard for retention and graduation rates even as it struggled amidst fluctuating funding. In 2015, however, the program received a $1.1 TRIO Student Support Services Grant—an award pursued and secured by then-Vice Provost for Student Success Tracy Pascua Dea and then-HP faculty co-director Gloria Aquino Sosa. Through the efforts of Dea, Sosa, then-HP Director Tarik Scott, High Potential was able to reimagine itself "as a strengths-based integrated program with full-time dedicated staff, evidence-based practices, and increased scholarships to eligible students," says Jenee Palmer, who served as High Potential's Director from 2018 to 2021.

In 2020, Palmer, Dea, and Sosa secured another TRIO grant of $1.5 million. To date, it is the largest amount HP has ever been awarded. The grant allowed High Potential to continue reinforcing and expanding its suite of assistance services, strengthening the program’s “interconnected view of students’ success,” Megan Mustain, then-vice provost for Student Academics, said in 2020. TRIO, she said, “fosters academic excellence by recognizing and celebrating the strengths that first-generation and low-income students bring to Saint Mary's."

“Fifty years ago, students of color and their allies were occupying this Chapel, trying to make Saint Mary's a more inclusive community,” says Tom Brown. “They and I could never have imagined.”

A Badge of Honor

For Torres, the most striking shift she has tracked while researching High Potential is a change in self-perception. In the early days, students in the program might have kept that to themselves. But no longer. “Now, we're willing to speak up about it and have some pride in the fact that we are first-gen,” she says. “We are accomplishing something.”

That evolution is something Soine, who was teaching the Public History course, hoped her students would recognize as they captured the history of HP. “I think that it was important for them to realize how HP students and alums really changed that image themselves,” she says. “They really exemplify what it means to have a Saint Mary's education.”

Certainly, Brown, Hernandez, “Dr. D,” and all the High Potential leaders who have followed since have blazed educational trails. “The things that were happening in the High Potential Program really became best practices for higher education,” Soine says. But ultimately, she notes, it’s students who led the way—a truth that feels core to the mission of the College. “It’s really a badge of honor that these are the best of our students."

These days, members of High Potential consider themselves a family—and last fall, Torres and Soine got to experience something of a family reunion. On November 11, 2023, generations of first-generation and low-income students and leaders gathered in the Soda Center to celebrate the Program’s 50th anniversary. Many of those present were alums that Soine’s Pubic History students interviewed, along with past HP directors like Maria Hernandez and Tom Brown. For months, Torres and her classmates had pieced together the arc of the program, filling in the archival silence. Now, history was echoing all around them: mingling, embracing, and reconnecting over the made-to-order omelets.

Later during the reunion, HP’s current director, Chameeta Denton MA ’10, stepped up to the microphone, expressing gratitude for those gathered and outlining her vision for the next chapter of High Potential: connecting current students with alumni mentors. “It's so important, as you all know, to pass the baton to the next generation of students,” she said. “Once we've done this, we can build a coalition that is unstoppable and one that people cannot choose to ignore.”

Brown sat in the front row, beaming and nodding. Later, he tells me about an epiphany he had at the memorial service of his dear friend, Brother Camillus Chavez ’57, one of HP’s spiritual guides and leaders. Brother Camillus passed away on May 31 of last year, and his service was held a few days later at Saint Mary’s. The Chapel was “packed,” Brown says, and as the memorial got underway, “I was smiling the whole time.” Brown listened to a Mariachi band and watched two High Potential alums place a sarape blanket over the coffin. As the crowd in read liturgies in both Spanish and English, Brown couldn’t help thinking back to 1972.

“I was smiling because, fifty years ago, students of color and their allies were occupying this Chapel, trying to make Saint Mary's a more inclusive community consistent with its Lasallian heritage,” he says. “They and I could never have imagined.”

Not that the story is over, Brown says. “The High Potential Program has persisted, so I’m encouraged. But I’m never satisfied.” Perhaps that’s the stone-cold revolutionary talking.

Hayden Royster is Staff Writer at the Office of Marketing and Communication for Saint Mary's College. Write him.